The Roll

The die sits on the hospital tray like a tumor made of plastic. Six sides. Six decades, maybe. Or six months.

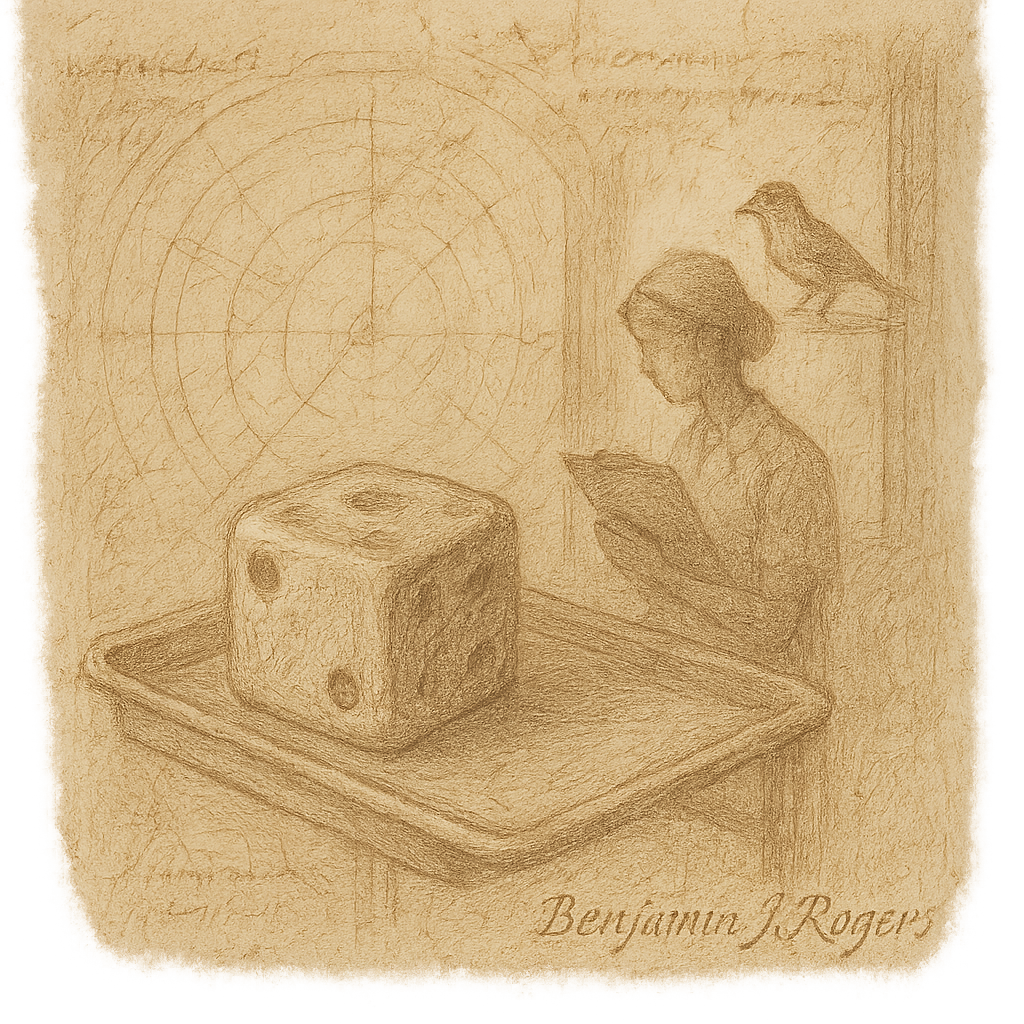

Martha's fingers hover above it - liver-spotted, trembling from something deeper than age. The nurse waits by the window, clipboard pressed against her chest like armor. Outside, a sparrow lands on the sill, cocks its head, and flies away.

"The system's fair," Dr. Chen had said, adjusting his glasses with the practiced ease of a man who'd never rolled. "Random distribution. No bias toward wealth, status, genetics." His voice carried the hollow ring of someone quoting policy. "Everyone gets their chance."

Their chance.

Martha thinks of her grandson, Tommy, who rolled a four last Tuesday. Four years. He'd laughed - actually laughed - and asked if he could have ice cream for breakfast now. His mother cried into dish towels for three days.

The die catches the fluorescent light. Cheap plastic, probably made in some factory where workers roll their own dice at sixteen, get their numbers, plan accordingly. Or don't plan. What's the point of a 401k when you might roll snake eyes?

"Mrs. Patterson?" The nurse's voice is gentle, rehearsed. How many times today? How many dice sit on how many trays in how many rooms?

Martha remembers when people died of things. Cancer. Accidents. Time. Now they die of mathematics. The Randomization Act passed when she was forty - old enough to be grandfathered in, young enough to watch her children grow up knowing their expiration dates.

Her daughter rolled a five. Fifty years. Reasonable. Manageable. She bought a house, had Tommy, divorced his father when she calculated she couldn't waste time on lukewarm love.

Tommy's father rolled a two.

Martha picks up the die. It's lighter than expected, hollow maybe, like everything these days. She thinks of prayers - not to change the outcome, but for grace to accept it. Six sides. Each one a different weight of grief.

The sparrow returns to the window.

She closes her eyes and lets gravity decide.

The die tumbles across metal, sound sharp as winter. When it stops, she doesn't look. Instead, she watches the sparrow tap the glass with its beak - once, twice, three times - before vanishing into the boundless, unmeasured sky.

The nurse writes something down.

Martha still doesn't look.

Outside, the world spins on, indifferent to numbers, dice, and the small mathematics of mortality. She thinks this might be the point - not the rolling, but the moment after, when you choose what to do with whatever time the universe has dealt you.

Even if it's only long enough to count to six.